Poetic Reflections: A Pilgrimage to Keats’s Grave by Matthew J. Clarke

The K-SAA Poetic Reflections series invite readers to re-introduce, re-read, or reflect upon an author from the Keats-Shelley Circles. We encourage our members and followers to send in their own reactions to that reading. We welcome contributions to this series, so please do get in touch if you’d like to get involved and share your ideas with us.

Today we welcome a new contributor, Matthew J. Clarke, who writes on the grave of John Keats in Rome. Read more about the Non-Catholic Cemetery, where both John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley are buried, on their website here. Want more specifically on Shelley’s grave from the K-SAA Blog? Have a read of this post from 2018. But first! Continue reading for Clarke’s new consideration of poetic legacy and memory, covering Sarah Helen Whitman, Oscar Wilde, Thomas Hardy and more contemporary responses, too!

A Poetic Pilgrimage to Keats’s Grave

Keats’s Grave by William Bell Scott (Ashmolean)

The grave of John Keats remains one of the most enduring landmarks of literary pilgrimage. Over two centuries many have adhered to Percy Shelley’s entreating in Adonais to ‘Go thou to Rome’ (433) to that city in which Keats, stricken with consumption, anticipated the pall of daisies that would grow over him. Shelley, whose ashes were interred in a nearby plot after drowning off the coast of Lerici in 1822, would only further cement the poetic appeal of the Cimitero Acattolico.

The years following Keats’s death saw an outburst of tributary verse from both sides of the Atlantic, as poets sought to preserve a legacy seemingly threatened by the critics of his day. One of these earlier tributes from the American poet Sarah Helen Whitman, with her 1859 poem ‘A Pansy from the Grave of Keats’, describes a visit to Keats’s ‘far Italian tomb’ (55). While it is uncertain whether Whitman herself journeyed to Rome, the title’s allusions to the tradition of picking flowers from the grave, which would have been returned home or sent to loved ones, suggests possible explanations for her familiarity with the grave. Taking this tradition, Whitman expands it as an analogy for Keats’s poetry; his works are ‘Transferred to daylight’s common beam’ (59), becoming the ‘pansies’ (54) which now adorn his grave. Each paragraph alludes to one of Keats’s ‘velvet petals’ (1), all ‘legended with faery lore’ (8) which, despite many being ‘left half told’ (25), remain, like his life, ‘A Beauty and a Joy forever’ (61). The poems, like the flowers, are gathered and decorated on top of his grave along with Whitman’s own, itself transfigured as another ‘Pansy’ from his grave.

Oscar Wilde, visiting Rome in 1877, detailed his visit to the grave in his sonnet and accompanying article for the Irish Monthly. Wilde here echoes the early myth of the martyred poet, only extricated from his ‘pain’ and ‘the world’s injustice’ (1) through his premature death. For all the injustice he endured, Keats is canonised by Wilde, ‘Fair as Sebastian, and as early slain’ (5). Describing the grave, Wilde notes the absence of cypress trees and ‘funeral yew’ (6) but the abundance of ‘gentle violets’ (7), which prove, as noted in his essay, ‘poor memorials’ to Keats’s memory. Wilde plays with Keats’s famous epitaph – ‘Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water’ – to be the tears, like the poet’s own, of the mourners who congregate at his grave ‘As Isabella did her Basil-tree.’ (14) Mourners and poets thus become intimately involved in keeping ‘thy memory green’ (13), instrumental to preserving a poetic legacy seemingly threatened with obscurity.

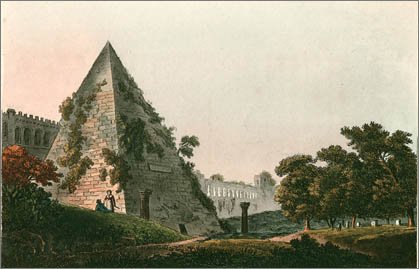

The Pyramid of Gaius Cestius in the Non-Catholic Cemetery

A decade later saw Thomas Hardy make his journey to Italy, seeking the presence of past poets to affirm his status as a poet. Hardy not only brought back some of the precious violets from the grave that March of 1887 but also the poetic germs which would later comprise ‘Poems of Pilgrimage’ in Poems of Past and Present (1901). Despite the significance of his trip to the Protestant Cemetery, his poem ‘Rome at the Pyramid of Cestius Near the Graves of Shelley and Keats’, makes no direct mention to either Keats or Shelley, instead directing his focus to the contiguous pyramid of Gaius Cestius. The tomb of the Augustan magistrate, described by Shelley as standing ‘like flame transformed into marble’ (447), is here diminished as merely ‘a pyramid’ (8) of no personal value to the poet: ‘Who, then, was Cestius, / And what is he to me?’ (1-2). Instead, Hardy grants his ‘ample fame’ (24) in ‘beckoning pilgrim feet’ (17) to where his ‘Two countrymen’ (12) reside. The poem’s ambivalent tone also suggests Hardy’s anxiety towards the fates of Keats and Shelley’s memories, in which his own as a poet would be compromised. While assigning a personal reverence to the site, there remains the fear that the ‘two immortal Shades’ will likewise transcend their ‘first design’, falling into obscurity to someday ‘mark’ (23) the presence of another.

The Keats-Shelley House, Rome

In 2015, the contemporary poet, John Challis, took residence at the Keats-Shelley House in Rome, the same house by the Piazza di Spagna in which Keats died and later preserved as a museum and library in 1906. Of the poems inspired by his residency, his ‘The Light in Rome’ offers a direct line through, while leaving his own mark in, this tradition of Keatsian pilgrimage. The poet, on a self-professed ‘pilgrimage’ (16), tells of his pursuit of ‘some phantom wit’ (10) eluding him, ‘a faint of light that burnt brightest years ago’ (23). He hopes, in pursuing this spectral presence, to ‘decipher’ what his antecedents meant as much as ‘tell what I mean too’ (12). Challis confesses an anxiety of influence having, ‘like all elegists’ (7), ‘borrowed’ (8) heavily from his predecessors, with the price of imitation costing ‘more than cash’ (9). He fears living in the shadow of these great poets, and yet holds onto his convening with the past in the ‘faith that the next draft may / exceed the last’ (13-14). While Challis meditates on his anxieties towards ascertaining this light, fearing he lacks the ‘tools’ to harness something ‘Too physical for truth’ (30), his poem closes with a collective vindication:

“[…] To go where we have gone

and give ourselves piecemeal to youth

who carry on the search for truth that we,

in each our splendid ways, failed to complete.”

This search, then, is justified in offering ourselves to the young poets who, as Shelley closes Adonais, now inhabit ‘the abode where the Eternal are.’ (495)

This desire to pay homage and communion lies at the very heart of these works. As much as poets have brought offerings to Keats’s memory through tears and elegies, they have also sought to take something away, be that a flower from his grave else answers to what it means to be a poet. It is this reciprocity that lies at the heart of Keats’s ‘posthumous existence’ which, 200 years on, will continue to endure.

Works Referenced:

Challis, John, ‘The Light in Rome’, in Eborakon, 1.2 (2015)

Hardy, Thomas, The Complete Poems, ed. by James Gibson (London: Macmillan, 1976)

Matthews, Samantha, Poetical Remains: Poets’ Graves, Bodies, and Books in the Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

Roe, Nicholas, John Keats: A New Life (London: Yale University Press, 2012)

Shelley, Percy Bysshe, The Major Works, ed. by Zachary Leader and Michael O’Neill (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003)

Whitman, Sarah Helen, Poems (Boston, MA: Houghton, Osgood and Company, 1879)

Wilde, Oscar, ‘The Tomb of Keats’, Irish Monthly, 5 (1877), 476-478

Matthew Clarke is a writer and poet based in Cambridge, UK.

He graduated from Royal Holloway, University of London with a BA in English and History. In 2020, he was awarded an MA in Romantic and Victorian Literary Studies from Durham University. This past year, Matthew has written and presented papers on Percy Shelley and Henry Kirke White.

Read more on the cemetery and Keats and Shelley’s graves in work by Nicholas Stanley-Price, here and here.