Uncovering the Archive: Racial Politics in Humphry Davy’s Notebooks

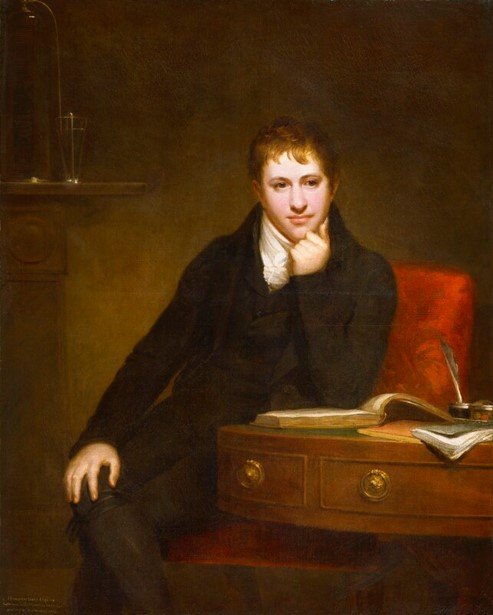

Sir Humphry Davy, Bt, by Henry Howard, oil on canvas, 1803, NPG 4591, National Portrait Gallery, reproduced with the permission of a Creative Commons license

Humphry Davy (1778-1829) is remembered today as a leading man of science. Yet his statue in Penzance has become the subject of controversy in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement. There are also statues of Davy on the top of Burlington House and in the Natural History Museum, Oxford, as well as numerous street names and buildings named after him. These monuments raise questions about how we remember Davy today, and makes it essential to examine his connections to historical slavery and his racial politics.

Humphry Davy’s statue, Market Jew Street, Penzance, Wikimedia commons

Davy is best-known for isolating seven chemical elements, more than any other individual, and invented a miners’ safety lamp, known as the ‘Davy Lamp’. Davy was also a poet, and Wordsworth, Southey, Byron, and Coleridge were part of his network.

A new AHRC-funded project, Humphry Davy’s Notebooks: How Poetry Helped Shape Scientific Knowledge, will produce the first completely fully transcribed collection of Davy’s entire notebook collection of seventy-five notebooks. Using the online platform, Zooniverse, members of the public are producing crowdsourced transcriptions of these notebooks.

The notebooks make clearer than ever before that Davy had connections to plantations in Antigua through his wife Jane Davy (1780-1855). Her wealth enabled him to focus on his chemical research and retire from the Royal Institution professorship in 1812. His brother, John Davy, lived in Barbados 1845-1848 as the Inspector General of Hospitals, published The West Indies, Before and Since Slave Emancipation and kept journals of his time in the West Indies.

HD/13/C, 11, poem ‘The blue flower neglected on the mountain.’ Davy’s notebooks are heterogeneous spaces, which contain poetry, records of his experiments, draft lectures and many other generically-mixed forms of writing.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and UCL’s Legacies of British Slave-Ownership database are key starting points for research into the Davys’ connections to historical slavery. Jane Davy, formerly Apreece (née Kerr), was born in Antigua and inherited money from her father, Charles Kerr who left half of his money to Jane and half to her mother when he died in 1795.

Jane’s father had been a merchant and navy agent in St John’s, Antigua. Jane was a widow by the time she met Humphry, having been married to Shuckburgh Ashley Apreece on 3 October 1798. In his letter to his mother before his marriage, Humphry Davy described Mrs Jane Apreece as having ‘an ample fortune’ (Collected Letters, vol 2, 159-60) and it was rumoured that she had an income of £4000 per year. Jane Davy’s mother, Jane Kerr remarried in January 1798 to Robert Farquhar (1756-1836), and they lived at 13 Portland Place in London.

Jane Davy’s stepfather, Robert Farquhar, was an absentee slave-owner in Antigua and Grenada, who received almost £19000 compensation from the government following the Slavery Abolition Act passed in 1833, which came into force the following year, and the Slave Compensation Act of 1837. Robert Harvey left his plantations in Antigua to his nephew Robert Farquhar in his will of 1790, by which time Farquhar is already described as a ‘planter’ in Antigua.

Evidence of the plantation records on the UCL database show that these plantations were being expanded in terms of increasing numbers of enslaved people in the 1820s, during the years of the Davys’ marriage. Jane Davy’s half-sister, Lady Eliza Mary Shaw-Stewart (née Farquhar) born in 1798 at Portland Place, went on to inherit her father’s fortune.

HD/20/C, 1, Expt 4, experiments on galvanic action

The connections of Jane and Humphry to Portland Place, the Farquhars and their interconnecting family and friendship circles is yet to be fully examined. Portland Place was significant in both of Jane Davy’s marriages. When she married her first husband, Apreece, on 3rd October 1798, Jane is described as ‘Miss Kerr, daughter of Mrs Farquhar, of Portland Place,’ and Jane and Humphry were married on 11 April 1812 at Portland Place by the Bishop of Carlisle (6 Oct 1798 and 13 May 1812, both Morning Post, Burney Newspapers). In a letter to the publisher, John Murray, on 5 June 1829, shortly after Humphry’s death, Jane Davy requested that seven copies of the second edition of Salmonia or Days of Fly Fishing would be sent as gifts from John Davy, and Robert Farquhar heads the list of recipients (Collected Letters, vol 4, 192-4).

Further research will be undertaken with the registers of enslaved people, 1817-34, that exist for the estates in Antigua and Grenada, to draw out the available evidence about who these enslaved people were and biographical details about them.

Jane’s wealth helped support Davy’s chemical research after 1812 and retire from his Royal Institution professorship. Jane also made efforts to preserve Davy’s legacy as a man of science in the weeks and months after his death on 29 May 1829.

Jane had commissioned a painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence in 1821, and after Davy’s death, gifted this to the Royal Society to be hanged in their rooms. Writing to Davies Gilbert, the President of the Royal Society, Jane emphasised her expectations of the handling of her gift to them, ‘making its place and its care a duty and a pleasure’ (Collected Letters, vol 4, 208-9). She paid £142 for a plaque at Westminster Abbey.

While these efforts are well known, letters recently collected in the 2020 four-volume edition of the Collected Letters of Humphry Davy, reveal several other ways in which Jane sought to preserve her husband’s memory in his networks and among a closer circle of family members. Jane corresponded with Davy’s sister Katherine Davy, noting that she would ensure Katherine and her sisters would be presented with ‘some Tokens you can always keep & wear’ (Collected Letters, vol 4, 195). Monetary bequests were made to Penzance Grammar School on the condition that the boys had an annual holiday on Davy’s birthday, on 17th December, and Jane offered an equivalent sum of £100 to be given to the Academy of Geneva.

HD/14/I, 19, sketch of a fish, in a notebook containing notes for ‘Salmonia’

The connections between the Davys’ and historical slavery, their links to Portland Place and the Farquhar family need to be examined as a key context for Davy’s scientific and literary achievements, and part of our discussion of how we remember Davy today. This is a key context for examining the notebooks, and as more of these notebooks are transcribed, more details of Davy and his racial politics will surely come to light.

Dr Eleanor Lucy Bird, Research Associate, Davy Notebooks Project.

Contact Dr Bird at e.l.bird@lancaster.ac.uk, or on Twitter here. The Davy Notebooks Project can be found on Twitter here.

Eleanor Lucy Bird is a Research Associate on the AHRC-funded Davy Notebooks Project in English Literature and Creative Writing at Lancaster University. She completed her PhD on Canada and Slavery in Transatlantic Print Culture at the University of Sheffield in 2018 and has published articles on Mary Prince and Susanna Moodie in Notes & Queries, and on slavery in Quebec’s newspapers (forthcoming in 2021) in the Journal of Transatlantic Studies. She is currently researching Humphry Davy’s racial politics and connections to the transatlantic slave trade and slavery.