"Race, Pedagogy, and Whiteness in the Long 18c: A Teach-In"

The Teach-In summarized here took place on August 6th, 2020, as professors of the long eighteenth century at a number of U.S. Universities prepared to begin the semester. We found the content and approach very helpful, and we hope you will too. Organizers: Shelby Johnson (Florida Atlantic University); Misty Krueger (University of Maine, Farmington); Kate Ozment (California State Polytechnic University, Pomona); Kristen T. Saxton (Mills College); Kerry Sinanan (UT San Antonio)Speakers: Shelby Johnson, Brigitte Fielder, Kerry SinananSee the full recording with closed captions Johann Zoffany's painting of Dido Elizabeth Belle and her cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray, 1779. Used as cover art for Lyndon J. Dominique's edition of The Woman of ColourSummary by Mariam WassifSEE BELOW FOR A LIST OF RESOURCES AND LINKSIntroductionThe familiar email opener “In these unprecedented times…” has become an online joke: “remember precedented times?” With no historical reference for the present circumstances, we are called upon to question the structures that once organized our lives, including our teaching. Not only does the COVID-19 pandemic present unique challenges to the logistics of teaching, especially in the United States, but the racial reckoning sparked by protests against anti-Black hate crimes necessitates, as Kerry Sinanan puts it, a re-examining of the link between “the culture hegemony of whiteness” and structural violence against marginalized communities. It is undeniable that academia, including the field of Romanticism, participates in this cultural hegemony. Among similar initiatives, the recent teach-in on “Race, Whiteness, and Pedagogy in the Long Eighteenth Century,” co-sponsored by the University of Texas, San-Antonio and Mills College, offers an opportunity for rethinking our pedagogical and methodological practices to meet the challenges of this moment of “intense crisis.”The teach-in gathered scholars specializing in the long eighteenth century in the Atlantic world (encompassing Britain, North America, Africa, and the Caribbean) as well as scholars in Shakespeare, Early Modern, Latinx, and De-colonial Studies. It came about as result of informal conversations between professors of the long eighteenth century, who wondered how to prepare courses for the fall semester in the context of ongoing racial violence and the impact of Covid-19 on Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities. As an attempt to answer that question, the teach-in proposes a model for learning together, eschewing any claims of expertise. Following an introduction by Kerry Sinanan, the online seminar included a talk on early African-American literature by Brigitte Fielder, a talk on pedagogical practices by Sinanan, and a discussion of indigenous literature by Shelby Johnson. The seminar concluded with breakout group discussions, which were not recorded.In her introduction to the seminar, Kerry Sinanan emphasized the need to “think more deeply about our disciplinary boundaries and pedagogies.” Sinanan modeled examples of “transformative pedagogies” that can allow teachers to acknowledge that classrooms, whether virtual or physical, do not exist in a vacuum. Our students not only learn in the context of political and environmental conditions that are especially pressing at this time, but also bring to the learning space their lived experience and embodied being. Practices such as naming recent Black victims of hate crimes, like George Floyd or Black trans women Nina Pop and Tatyana Hall, or making land acknowledgements in the case of U.S., Canadian, and Australian universities, can allow learning spaces to intersect with the broader world in productive ways. As Sinanan emphasized, such gestures are hollow when not backed by actions such as donating to initiatives like those listed below. Meanwhile, “wellness checks” implemented by some professors or breathing exercises such as that modeled by Sinanan, in which students are asked to breathe in and out while extending compassion for victims and for themselves, can serve as powerful reminders of learning as a gathering not just of minds but of embodied and feeling beings.Such strategies, when practiced with great care, can help situate learning spaces within the broader world. This itself is an example of the “undisciplining” the seminar emphasized—breaking the illusion of clear boundaries that demarcate the learning space from everywhere else.Citing thinkers like Christina Sharpe and Toni Morrison, Sinanan makes a case for “undisciplining” in the sense of both eliminating carceral practices from pedagogy, and rethinking the disciplinary boundaries of the research that feeds this pedagogy. In her essay Playing in the Dark, Morrison warned against moving African and African-American studies into a different realm, and thereby segregating disciplines. As Sinanan points out, the word discipline—whose oldest meaning is an area of study, a system of rules and regulations, and a body of rules—“conjoins teaching with punishment, disciple with discipline.” Undisciplining as an approach to research and pedagogy thus draws upon the present surge in support for police and prison abolition and relies on the example of disobedience of Black Lives Matter protestors. Along with the implications for pedagogy, such an approach highlights that a more global perspective is an important way forward for Romanticism and long eighteenth century studies, as scholars who take this approach have long argued.Brigitte Fielder on Belinda's Petition

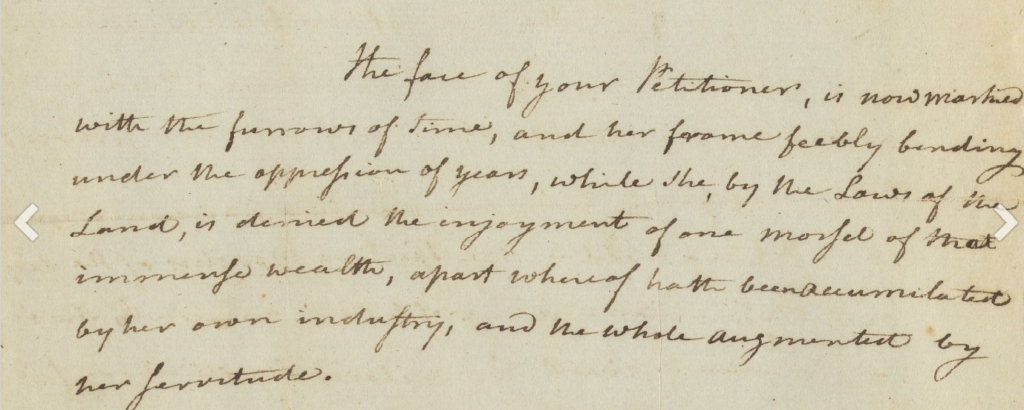

Johann Zoffany's painting of Dido Elizabeth Belle and her cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray, 1779. Used as cover art for Lyndon J. Dominique's edition of The Woman of ColourSummary by Mariam WassifSEE BELOW FOR A LIST OF RESOURCES AND LINKSIntroductionThe familiar email opener “In these unprecedented times…” has become an online joke: “remember precedented times?” With no historical reference for the present circumstances, we are called upon to question the structures that once organized our lives, including our teaching. Not only does the COVID-19 pandemic present unique challenges to the logistics of teaching, especially in the United States, but the racial reckoning sparked by protests against anti-Black hate crimes necessitates, as Kerry Sinanan puts it, a re-examining of the link between “the culture hegemony of whiteness” and structural violence against marginalized communities. It is undeniable that academia, including the field of Romanticism, participates in this cultural hegemony. Among similar initiatives, the recent teach-in on “Race, Whiteness, and Pedagogy in the Long Eighteenth Century,” co-sponsored by the University of Texas, San-Antonio and Mills College, offers an opportunity for rethinking our pedagogical and methodological practices to meet the challenges of this moment of “intense crisis.”The teach-in gathered scholars specializing in the long eighteenth century in the Atlantic world (encompassing Britain, North America, Africa, and the Caribbean) as well as scholars in Shakespeare, Early Modern, Latinx, and De-colonial Studies. It came about as result of informal conversations between professors of the long eighteenth century, who wondered how to prepare courses for the fall semester in the context of ongoing racial violence and the impact of Covid-19 on Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities. As an attempt to answer that question, the teach-in proposes a model for learning together, eschewing any claims of expertise. Following an introduction by Kerry Sinanan, the online seminar included a talk on early African-American literature by Brigitte Fielder, a talk on pedagogical practices by Sinanan, and a discussion of indigenous literature by Shelby Johnson. The seminar concluded with breakout group discussions, which were not recorded.In her introduction to the seminar, Kerry Sinanan emphasized the need to “think more deeply about our disciplinary boundaries and pedagogies.” Sinanan modeled examples of “transformative pedagogies” that can allow teachers to acknowledge that classrooms, whether virtual or physical, do not exist in a vacuum. Our students not only learn in the context of political and environmental conditions that are especially pressing at this time, but also bring to the learning space their lived experience and embodied being. Practices such as naming recent Black victims of hate crimes, like George Floyd or Black trans women Nina Pop and Tatyana Hall, or making land acknowledgements in the case of U.S., Canadian, and Australian universities, can allow learning spaces to intersect with the broader world in productive ways. As Sinanan emphasized, such gestures are hollow when not backed by actions such as donating to initiatives like those listed below. Meanwhile, “wellness checks” implemented by some professors or breathing exercises such as that modeled by Sinanan, in which students are asked to breathe in and out while extending compassion for victims and for themselves, can serve as powerful reminders of learning as a gathering not just of minds but of embodied and feeling beings.Such strategies, when practiced with great care, can help situate learning spaces within the broader world. This itself is an example of the “undisciplining” the seminar emphasized—breaking the illusion of clear boundaries that demarcate the learning space from everywhere else.Citing thinkers like Christina Sharpe and Toni Morrison, Sinanan makes a case for “undisciplining” in the sense of both eliminating carceral practices from pedagogy, and rethinking the disciplinary boundaries of the research that feeds this pedagogy. In her essay Playing in the Dark, Morrison warned against moving African and African-American studies into a different realm, and thereby segregating disciplines. As Sinanan points out, the word discipline—whose oldest meaning is an area of study, a system of rules and regulations, and a body of rules—“conjoins teaching with punishment, disciple with discipline.” Undisciplining as an approach to research and pedagogy thus draws upon the present surge in support for police and prison abolition and relies on the example of disobedience of Black Lives Matter protestors. Along with the implications for pedagogy, such an approach highlights that a more global perspective is an important way forward for Romanticism and long eighteenth century studies, as scholars who take this approach have long argued.Brigitte Fielder on Belinda's Petition Source: Royal House & Slave QuartersIf Sinanan’s introduction calls for a breakdown in the boundaries of regional specialization as well as those of power in pedagogy, Brigitte Fielder’s intervention on early African-American literature interprets undisciplining not only as a means of correcting the White Western individualist approach to literature, which isolates the individual from contemporaneous and intergenerational community, but also of rethinking the genres that fall under the reach of literary study. The notion that literature as belles lettres, or “fine letters,” encompasses primarily texts with purely aesthetic purposes can lead to the exclusion of texts by Black writers of the long eighteenth century. The conventional understanding of Romanticism as a poetic phenomenon—which retains a hold on the field—is a case in point. Fielder focuses on the genre of the petition, and more specifically the text commonly known as “Belinda’s Petition,” the 1783 petition of Belinda Sutton to the Massachusetts General Court, in which the former enslaved woman asked for compensation from her former enslavers and thus made an early case for reparations. Contrasting with the narratives of exceptionalism and firstness of which Romanticism is a key source, Fielder argues that “thinking relationally and inter-generationally about early Black literature” not only lends itself to “a more capacious understanding” of these authors and their literary moments, but can also guide our twenty-first century engagements with them and make our pedagogical choices “more transparent to our students.” In her petition, Belinda Sutton reaches into the past to describe being torn from her parents and enslaved, but also looks forward to the “comfort” that compensation would scatter over the “downward paths” of her and her daughter’s lives. However, the intergenerational significance of the petition goes beyond Sutton’s concern for her daughter, extending into the “centuries-long project of recovering the text” through methodologies of research into early African-American literature. This project of recovery involves rescuing the text from misreadings engendered by efforts to understand it in relation to whiteness—for instance, by focusing on the possible amanuensis of the unlettered Belinda or presuming that the petition is a fiction of White anti-slavery activists. The methodologies of African-American literature evoked by Fielder allow instead for the text to be conceived as one belonging to a Black community, and thus reframe it for future generations of readers. Recovery is therefore an act of “radical hope that extends print technology’s reach into our imagined future.”Kerry Sinanan on Undisciplined Pedagogy

Source: Royal House & Slave QuartersIf Sinanan’s introduction calls for a breakdown in the boundaries of regional specialization as well as those of power in pedagogy, Brigitte Fielder’s intervention on early African-American literature interprets undisciplining not only as a means of correcting the White Western individualist approach to literature, which isolates the individual from contemporaneous and intergenerational community, but also of rethinking the genres that fall under the reach of literary study. The notion that literature as belles lettres, or “fine letters,” encompasses primarily texts with purely aesthetic purposes can lead to the exclusion of texts by Black writers of the long eighteenth century. The conventional understanding of Romanticism as a poetic phenomenon—which retains a hold on the field—is a case in point. Fielder focuses on the genre of the petition, and more specifically the text commonly known as “Belinda’s Petition,” the 1783 petition of Belinda Sutton to the Massachusetts General Court, in which the former enslaved woman asked for compensation from her former enslavers and thus made an early case for reparations. Contrasting with the narratives of exceptionalism and firstness of which Romanticism is a key source, Fielder argues that “thinking relationally and inter-generationally about early Black literature” not only lends itself to “a more capacious understanding” of these authors and their literary moments, but can also guide our twenty-first century engagements with them and make our pedagogical choices “more transparent to our students.” In her petition, Belinda Sutton reaches into the past to describe being torn from her parents and enslaved, but also looks forward to the “comfort” that compensation would scatter over the “downward paths” of her and her daughter’s lives. However, the intergenerational significance of the petition goes beyond Sutton’s concern for her daughter, extending into the “centuries-long project of recovering the text” through methodologies of research into early African-American literature. This project of recovery involves rescuing the text from misreadings engendered by efforts to understand it in relation to whiteness—for instance, by focusing on the possible amanuensis of the unlettered Belinda or presuming that the petition is a fiction of White anti-slavery activists. The methodologies of African-American literature evoked by Fielder allow instead for the text to be conceived as one belonging to a Black community, and thus reframe it for future generations of readers. Recovery is therefore an act of “radical hope that extends print technology’s reach into our imagined future.”Kerry Sinanan on Undisciplined Pedagogy

Source: British Library

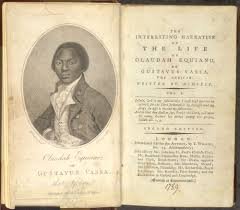

Following Fielder’s talk, Sinanan’s focuses on pedagogical practices more broadly. It is organized by four questions: 1) In what ways are our anti-racist and abolitionist pedagogies related to our context? 2) How can we center our students? 3) What does abolition and even radical love mean to our teaching practices? 4) How do we as teachers avoid being cops, and position ourselves instead as disobedient and undisciplined? The first question brings an earlier statement by Fielder about the need to “pull the threads of our readings into our current moment” to the pedagogical context, questioning how we can use the current “explosion of thought and energy”—or Fanonian “upheaval”—to promote urgent institutional change. That change, for Sinanan, begins with dismantling the inside/outside dichotomy of academia, which effaces students’ lives beyond the classroom and produces a hierarchical organization separating tenure-track and tenured faculty from adjunct and non-tenure-track academics and staff. In a time when the word abolition has become “common currency,” we can surely seek to abolish what is exploitative and oppressive in our own profession. The inside/outside dichotomy also structures canon formation and produces the “the Norton Anthology approach” to teaching and research. Challenging that polarity includes both centering “extra-canonical” texts by authors of color, and acknowledging the historical context of “canonical” works. For instance, we might read Swift’s “The Lady’s Dressing Room” as a poem not just about feminine beauty, but also about imperial consumption, as Hazel V. Carby argues in Imperial Intimacies. The second question of centering our students concerns how we encourage students to interrogate where they are “knowing from,” as well as how we situate them as inside or outside the long eighteenth-century intellectual tradition. Sinanan evokes Olaudah Equiano’s trope of the talking book, in which Equiano holds the book to his ear hoping it will talk to him, and is concerned that it remained silent. Without meaning to, Sinanan concludes, we can present the book as a “closed object” that neither speaks to the uninitiated “disciple” nor listens to its reader. Sinanan’s final two linked questions ask what abolition and radical love mean to our teaching practices, and how we can avoid positioning ourselves as cops who police the imagination. One answer, she proposes, is a transformation that values the creative individual, reading, writing, and working in a community moving toward abolition.Shelby Johnson on Indigenous Materials, Texts, and Methods Shelby Johnson’s talk picks up on Sinanan’s question of where we are “knowing from” by asserting that White colleagues should not present themselves as anti-racism experts, but deliberately as White scholars who must be part of a wider movement to dismantle the White supremacy in our field. Echoing Fielder’s earlier call for thinking communally about early Black literature, Johnson emphasizes collaboration as opposed to the “single genius model” favored by academia, as well as the need to acknowledge the transformative power of BIPOC leadership and scholarship. Johnson foregrounds native petitions as “foundational indigenous literature that is collaborative, consensus-based, and not singly authored, thus contesting emergent Romantic conceptions of authors and authorities.” Arguing for the need to incorporate texts and scholarship by native writers and artists, Johnson concludes by asking: How can indigenous materials, texts, and methods enable a reappraisal of English literary studies as a disciplinary formation? How has English as a discipline been complicit in indigenous dispossession?”ConclusionA particular strength of this teach-in is that it modeled the collaborative and inquisitive models the speakers advocated, with speakers raising questions and indicating directions rather than seeking to provide authoritative answers, and positioning themselves as learners as well as teachers. In that spirit, I want to emphasize that I include myself in my criticisms of academia and the fields of Romanticism and eighteenth-century studies, and view the writing of this essay partly as a process of self-education (after all, random men on Twitter are always telling me to EDUCATE MYSELF!). As an example of wider efforts to question disciplinary boundaries and pedagogical methods—including the recent Dickens Universe virtual conference focusing on Frances Watkins Harper and the anti-racism pedagogy series from the University of Maryland—“Race, Whiteness, and Pedagogy in the Long 18c” offers an opportunity for reflection as we begin a very fraught academic year. Such events are themselves acts of “radical hope” offering more anti-violent, communal, and even loving directions for our profession.Examples of How to Contribute

Shelby Johnson’s talk picks up on Sinanan’s question of where we are “knowing from” by asserting that White colleagues should not present themselves as anti-racism experts, but deliberately as White scholars who must be part of a wider movement to dismantle the White supremacy in our field. Echoing Fielder’s earlier call for thinking communally about early Black literature, Johnson emphasizes collaboration as opposed to the “single genius model” favored by academia, as well as the need to acknowledge the transformative power of BIPOC leadership and scholarship. Johnson foregrounds native petitions as “foundational indigenous literature that is collaborative, consensus-based, and not singly authored, thus contesting emergent Romantic conceptions of authors and authorities.” Arguing for the need to incorporate texts and scholarship by native writers and artists, Johnson concludes by asking: How can indigenous materials, texts, and methods enable a reappraisal of English literary studies as a disciplinary formation? How has English as a discipline been complicit in indigenous dispossession?”ConclusionA particular strength of this teach-in is that it modeled the collaborative and inquisitive models the speakers advocated, with speakers raising questions and indicating directions rather than seeking to provide authoritative answers, and positioning themselves as learners as well as teachers. In that spirit, I want to emphasize that I include myself in my criticisms of academia and the fields of Romanticism and eighteenth-century studies, and view the writing of this essay partly as a process of self-education (after all, random men on Twitter are always telling me to EDUCATE MYSELF!). As an example of wider efforts to question disciplinary boundaries and pedagogical methods—including the recent Dickens Universe virtual conference focusing on Frances Watkins Harper and the anti-racism pedagogy series from the University of Maryland—“Race, Whiteness, and Pedagogy in the Long 18c” offers an opportunity for reflection as we begin a very fraught academic year. Such events are themselves acts of “radical hope” offering more anti-violent, communal, and even loving directions for our profession.Examples of How to Contribute

- Donate to local indigenous communities or organizations

- Donate to bail funds for protestors

- Donate to Black Lives Matter

Resources Mentioned in the Teach-inPrimary Sources

- Belinda Sutton’s 1783 Petition

- The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, by Olaudah Equiano

- “The Lady’s Dressing Room” by Jonathan Swift, in The Poems of Jonathan Swift, vol. 2

- The Woman of Colour: A Tale (anonymous), edited by Lyndon J. Dominique

Pedagogy

- “Forget Distance Learning. Just Give Every College Student an Automatic A” by Jenny Davidson

- “Teaching To Transgress” by Bell Hooks

- “’Where Do You Know From?’: An exercise in placing ourselves together in the classroom” by Eugenia Zuroski

Criticism

- African-American Literature in Transition: 1900-1910 by Shirley Moody-Turner

- Black Skin, White Masks by Frantz Fanon [Fanon writes that there is a “zone of non-being,” “an utterly naked declivity where authentic upheaval can be born” (8)].

- The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast by Lisa Brooks

- Hortense Spillers round table [Spillers responds to Lorde’s essay, listed below]

- Imperial Intimacies: A Tale of Two Islands by Hazel V. Carby

- In the Wake: On Blackness and Being by Christina Sharpe

- “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” by Audre Lorde, in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (PDF online)

- Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination by Toni Morrison

- Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America by Saidiya Hartman

Further Resources

- Anti-racism Teach-In, The University of Maryland

- The bigger 6 collective (resources)

- “Everything Worthwhile is Done With Other People” by Mariame Kaba

- “Labor-Based Grading Contracts” by Asaoe B. Inoue

- “A Pedagogy of Kindness” by Catherine Denial

- “A Talk to Teachers” by James Baldwin, The Saturday Review, December 21, 1963, pp. 42-44

- The Virtual Dickens Universe 2020

- “Writing About Slavery? Teaching About Slavery?” by P. Gabrielle Foreman et. al.

- The Woman of Colour Facebook group

About the author, Mariam Wassif: I received my PhD from Cornell University in 2018 with a specialization in British literature of the long eighteenth century, including Romanticism. My published work has appeared in European Romantic Review, Philological Quarterly, and The Wordsworth Circle, and my book manuscript in progress is entitled “Poisoned Vestments”: Rhetoric and Material Culture in England and France, 1660-1820. I am currently a research and teaching fellow at the University of Paris 1- Panthéon-Sorbonne.