“Uncommon Engagements”: Commonplace Books in Primary Source Literacy Instruction

By Sandy Enriquez, Special Collections Public Services, Outreach & Community Engagement Librarian and

Carrie Cruce, Student Success and Engagement Librarian

University of California, Riverside

Introduction:

Commonplace books pose an interesting challenge in primary source literacy instruction. Although students are generally familiar with examining literature as text, examining the full object in all its materiality, and sense of process, can be new terrain for many. In Fall 2023, we developed an archives instructional session in collaboration with Professor Padma Rangarajan for the class ENGL 166T: Studies in English Romanticism. We designed the session so that students could engage with both the physical materiality and the intellectual content of commonplace books from UC Riverside Special Collections & University Archives. Our goal in this instructional session was to guide students through structured activities that combine hands-on engagement with analysis and reflection. In sharing our successes and challenges throughout this process, as well as our own reflections and musings on this experience, we hope to encourage more scholars to utilize commonplace books in their instruction and expand the range of possibilities when collaborating with Special Collections.

Background:

UCR has a student body of over 26,000 students, many of whom are the first in their families to attend college and come from historically underrepresented backgrounds. Most of our students are commuters, with the majority traveling to campus daily. UCR's diverse and dynamic student body is characterized by resilience and commitment, balancing academic pursuits with work, family responsibilities, and the challenges of commuting. Established in 1968, UCR SCUA focuses on five main collecting areas: Special Collections (arts & culture, local history, Latin American Studies, and the history of the Tuskegee Airmen), University Archives, the Eaton Collection of Science Fiction and Fantasy, the Water Resources Collections and Archives, and print materials (which encompasses rare books, journals, manuscript leaves, comic books, fanzines, and others, such as commonplace books).

We developed this session to emphasize hands-on practice and embodied learning, however class size is often the primary factor that dictates what activities and pedagogical strategies will be available when using special collections materials. This was a large class by SCUA standards (60 students enrolled). Generally, we aim to have 10-20 students per archive instructional session (up to 40 maximum with two instructors), due to the intensive needs and care & handling protocols that must be followed to ensure preservation of the materials. Yet, we do not wish to discourage large classes from utilizing special collections materials. Therefore, to meet this requirement, we taught two identical iterations of this class with half of the students at a time (~30 per session). This was also a “one-shot class” (meaning we taught a single session, rather than a series of sessions), so we could not devote ample time to any one particular activity, and instead had to strategically scaffold the learning objectives in creative ways to make the best use of our time.

Pedagogy & Activities:

One of the benefits of a special collections session in the library is the opportunity to provide students with a safe and accessible environment to experience the unique physical and material characteristics of an object firsthand. Generally, we guide their interaction and consideration of historical context, form and function, or symbolic relevance, all in relation to the material object in front of them. However, this approach, which focuses on the end product, lacks an experience of process. With an object like the commonplace book, understanding the process of its creation is crucial to comprehending how it functioned in context. The challenge, then, is how to offer an experience of process in a special collections session while keeping time, skill, budget, and safety in mind.

Setup

We decided to offer a combination of experiences: reading, selecting, and hand-copying text, as well as binding a book by hand. The class time was divided into four sections: introduction/care & handling (15 min), analysis worksheet (25 min), bookbinding exercise (30 min), and discussion (10 min). Students were divided into small groups of 4-6 per table, with 3 commonplace books per group. We were mindful to include a combination of both handwritten and typewritten books per table, accounting for the fact that students may be unaccustomed to reading handwriting and wanting to make this experience as inclusive as possible. We found that most students relied more heavily on the typewritten books to complete their worksheet assignment; but they still gravitated to exploring the handwritten books when time permitted. Some of these handwritten books were very challenging to decipher, either due to penmanship, language, or degradation. Despite these challenges, many students still found the organic and unique elements of the handwritten books compelling and they spent significant time examining them.

Worksheet

We created a custom worksheet that guided students on how to interact with the books, noting what material evidence to examine and what elements to explore. While initial iterations of this worksheet were more detailed and robust, we ultimately chose to pare it down to the foundational observations so that students could feasibly complete it in the given time (25 minutes total; 15 minutes for Part 1 and 10 minutes for Part 2), accounting for time to just explore and connect to the books. In particular, Part 1 (choosing a quote) can be a very subjective experience– some students will want to pick something that they identify with, and that type of evaluation can take time. We did not want students to be distracted by the worksheet and more concerned about finishing it than organically interacting with the book.

If more time is provided in future iterations, we would add in more elements to this worksheet depending on the learning objectives. For example, we might ask students to evaluate the condition of the book, and infer what that could mean about its usage, or research a person/place/thing mentioned in the books and consider its historical context alongside the material documentation, etc. There is ample potential in the use of commonplace books for this type of investigative learning, however instructors must also consider the level of familiarity each student has with this type of exploration, and leave appropriate time for students to process and engage. This call for intentional timing is echoed in the following section on the bookbinding activity; while 30 minutes may seem extensive for an activity that typically only takes 5-10 minutes with practice, it is necessary, because students are coming into this hands-on activity with varying types of backgrounds and levels of comfort. In our case, our estimates proved correct, as most students used up all the time we allotted for both the worksheet and activity.

Bookbinding Activity

The students’ main task was to browse each book and select 1-2 sentences from any book to copy onto a provided blank sheet, which would then be duplicated, combined, and bound, thereby allowing each student to create their own spontaneous commonplace book in-class. We did not expect students to fully understand and digest each book, but rather asked them to survey the variety of perspectives present, and select a snippet of something that resonated with them. In that way, students were encouraged to follow their interests, metaphorically extracting and remixing these texts in the process– creating their own commonplace practice. While each students’ book would have identical content curated by the entire class, they could still personalize their books by choosing their own covers in the bookbinding activity.

For simplicity, we chose the basic five-hole pamphlet as our bookbinding method. This also allowed us to utilize tools and materials from previous workshops. The bookbinding process involved folding, scoring, measuring, piercing, and sewing the sheets into the final pamphlet. Pictured below is the centerfold of the resulting commonplace book. Students had full liberty to decide how they wanted to copy their quote; some cited their quotes, while others did not, and some chose to embellish their handwriting, while others remained more natural. Many students remarked that this was the first time they had ever done such a “hands-on” activity at a UCR class, and while unexpected, it was very rewarding to see and take home their completed product.

Student-made commonplace book, 2023. Private collection.

The Books:

We designed the worksheet and bookbinding activities to provide students a very structured and manageable way to engage with these complex objects. Commonplace books are very multifaceted– not only in theme or subject matter, but also in format, language, type, origin, use, etc. The majority of books we utilized in this class were typewritten commonplace books, some of which were commercially published and some of which were privately published even as recently as 1983.

Below we briefly highlight the five handwritten commonplace books we utilized in this class, as they uniquely illustrate the impact and personality possible within this medium:

A commonplace book from a gentleman in Jamaica (or perhaps from a gentleman who died from “Jamaica fever”), detailing inner musings, observations, and important notes.

A French commonplace book containing notes on mechanics, economics, demographics, as well as secret recipes.

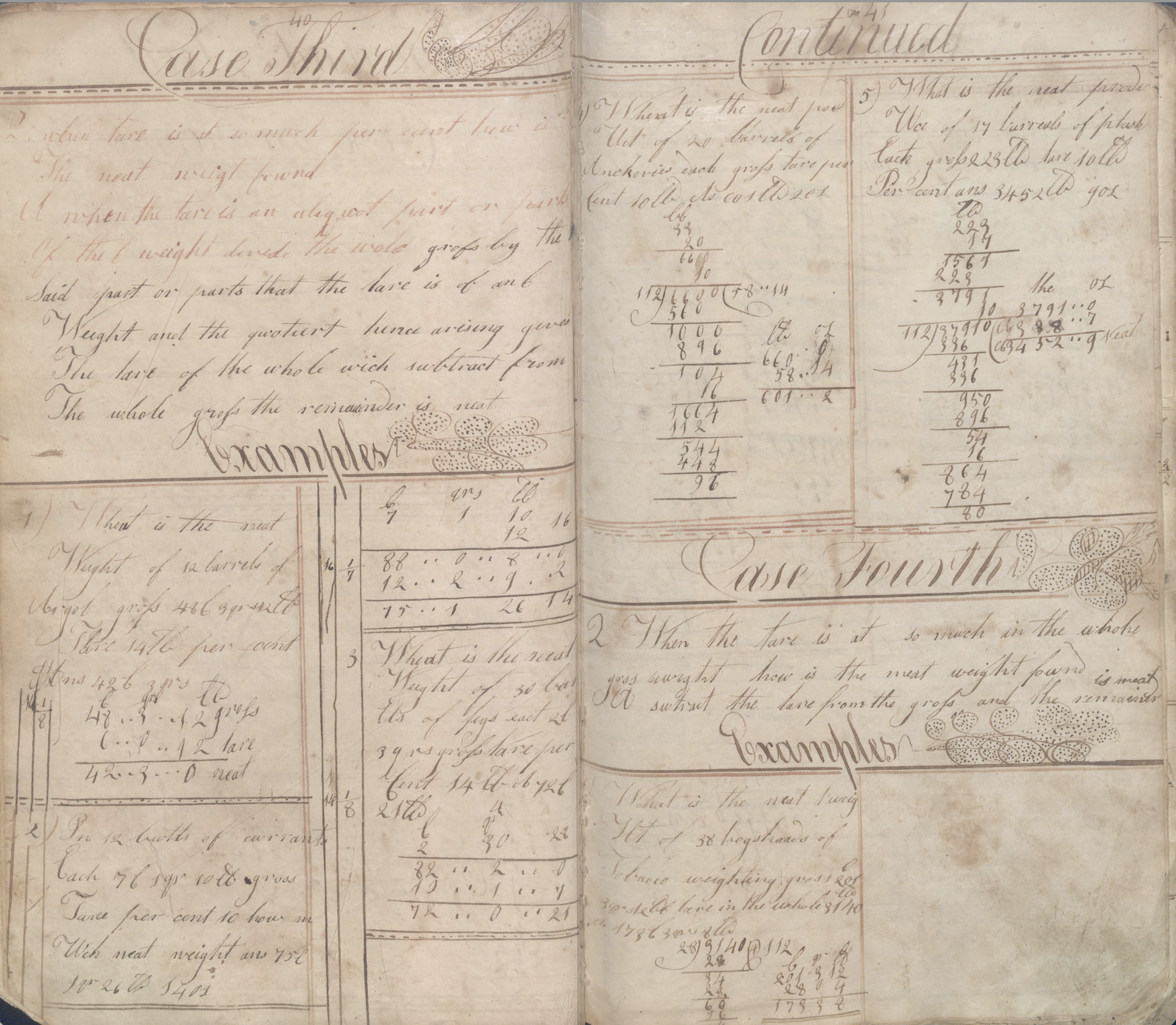

A neatly written commonplace book recording mathematics, scales, weights, prices for common goods, as well as doodling practice to draw a spotted bird.

A commonplace book tracking the weather and environment (locusts in England!) as well as drawings of architecture and people.

A gracefully written commonplace book attributed to Thomas Holland containing poetry in English and Latin, often written for individuals on special occasions such as weddings or funerals, as well as sketches of people and animals.

A full list of all the commonplace books used in this class is available here.

Commonplace book of a gentleman resident in Jamaica, ca. May 1817 - Nov. 1818. F1870.C66 1817. Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.

Commonplace book of a gentleman resident in Jamaica, ca. May 1817 - Nov. 1818. F1870.C66 1817. Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.

[French commonplace book], between 1827 and 1835. PN6246.F7 F74 1827. Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.

[French commonplace book], between 1827 and 1835. PN6246.F7 F74 1827. Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.

[Manuscript notebook showing definitions and examples of, and exercises in mathematics, as well as tables of weights and measures], 170-?. QA99.M26 1700. Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.

Close-Up Image of [Manuscript notebook showing definitions and examples of, and exercises in mathematics, as well as tables of weights and measures], 170-?. QA99.M26 1700. Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.

MS. Commonplace-book, 1820-1839. PN6245.D8 1839. Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.

MS. Commonplace-book, 1820-1839. PN6245.D8 1839. Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.

Commonplace book, 1792. PN6245.H65 1762. Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.

Commonplace book, 1792. PN6245.H65 1762. Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.

Reflection:

Many factors influenced the success of this class. Having two instructors to facilitate was helpful, as we could more easily transition between activities and supervise student engagement. For example, while one instructor supervised and facilitated the class, the other could take the students’ completed sheets to photocopy in preparation of the bookbinding exercise. Similarly, one instructor could clear fragile special collections materials so that students could smoothly move into the bookbinding exercise (which necessitated the use of awls and needles, materials we typically prohibit near rare books).

However, no class is without its challenges, and in this case, timing was a significant consideration. We had to encourage the students to speed up their copying of passages to allow enough time for the binding process. Additionally, there were natural differences among the students in their familiarity and experience with hands-on skills like sewing. Some students required more assistance than others, but ultimately, this also went smoothly as they helped each other, and both instructors were experienced with the five-hole pamphlet. In the future, streamlining the hand-copying of text to allow more time for the binding portion would be beneficial. Having additional instructors or student assistants would also help ensure that each student receives assistance promptly.

Hands-on, embodied learning (such as we have done here, combining bookbinding and archival instruction) can be a powerful tool for many classes, complementing traditional lecture instruction while giving students an opportunity to learn about a subject through a distinct tactile framework. Utilizing special collections materials can also be the most accessible way to start incorporating this type of active learning in the classroom. While we have each incorporated similar activities and pedagogies in other classes and workshops we’ve taught (such as journal or zine-making, and non-traditional printmaking through hectograph duplicators), striving to link hands-on practice with historical/cultural context, this is our first time utilizing the commonplace book as a focal point. We anticipate this type of instruction will be an area of growth for UCR Library, as we continue to explore similar hands-on learning through new library-led initiatives such as the UCR SCUA Mobile Print Workshop (funded by the Mellon Foundation and UCLA Radical Librarianship Institute), and other emerging projects.

This particular class was based in the department of English, however we envision this type of instruction could be adapted and offered to other programs, such as Comparative Literature and Languages, Media and Cultural Studies, Creative Writing, and History. Depending on the thematic content of the commonplace book, or if the identities of the authors are known, even fields such as Gender and Sexuality Studies or Environmental Science could be an option, but this may also be dictated by the quantity of books available (for example, at UCR Library only 2-3 of the commonplace books contain content relevant to these subjects, meaning digital surrogates or reproductions may need utilized when working with larger classes). Alternatively, a limited number of commonplace books could be placed on reserve for students to individually engage with in the special collections reading room as part of an asynchronous activity, perhaps after having attended an in-person instructional session. The possibilities are vast, given the appropriate notice, time, flexibility, and creativity.

Conclusion:

An interesting aspect to working with commonplace books is the sense of vulnerability inherent in these works. Although sometimes published for the masses, many commonplace books were kept private and personal, often containing the thoughts, opinions, musings, and knowledge of ordinary individuals. Commonplace books are perpetual works in progress, evident by their scribbled out mistakes, sketches practiced again and again, and entire pages ripped out. These aspects, while challenging, can be useful in helping teach students how to be critical thinkers. We asked them to consider the implications of how these items came to be preserved in the archive: did the creators know their works would eventually end up here, serving as objects of study for scholars and students alike? How do these complexities impact our interpretation of these works? While we can only speculate at what the original creators may have intended for their books, we can teach students to respect these unique items by examining them as material evidence of distinct historical, cultural, and social practices. Additionally, by engaging in some of the steps used to craft these works, we encourage students to connect with these books not only as historical artifacts but also as active examples of the process of living and creating the past.

About the Authors

Sandy Enriquez (she/hers) is the Special Collections Public Services, Outreach and Community Engagement Librarian at the University of California, Riverside Library. She works collaboratively to develop, manage, and implement robust public services operations, including coordinating outreach, programming, reference, access services, and instruction to foster the use of Special Collections and University Archives collections by the UCR community of faculty, scholars, researchers and students, in addition to the wider community of the Inland Empire. She earned her MA in Latin American Studies at New York University and her MLIS from Long Island University. She is Latina (Peruvian/Andean descent) and a first-generation/US-born heritage speaker of Spanish and Quechua. Her research interests include critical archival studies, print culture, and Andean Studies.

Carrie Cruce is the Student Success and Engagement Librarian at the University of California Riverside. As a member of UCR Library’s Teaching & Learning department Carrie is responsible for information literacy instruction as well as student outreach initiatives. She focuses on engagement and collaboration to promote the library as an active partner in student success. Carrie is dedicated to “meeting students where they are” and fostering a sense of student belonging in the library. As a librarian and educator, Carrie focuses on student-centered pedagogy. Carrie holds a BA with a focus on Art History from the University of Michigan, a MA in Art History from the University of Texas at Austin, and a MSIS degree in Information Science from the University of Texas at Austin. Her research interests include early 20th century German art, critical information literacy, visual literacy, and instructional design.