Rethinking Romanticism: Jane Alice Sargant: A Case Study for Nineteenth-Century Recovery Efforts

In this special “Rethinking Romanticism” and “Uncovering the Archives” series crossover, we are excited to welcome Dr. Emily J. Dolive to the blog. Here, Dr. Dolive discusses colonial campaigns, marginalized experiences, and the role of Jane Alice Sargent within this. See more entries from this series here. To write for this series, contact us.

Jane Alice Sargant: A Case Study for Nineteenth-Century Recovery Efforts

By Emily J. Dolive

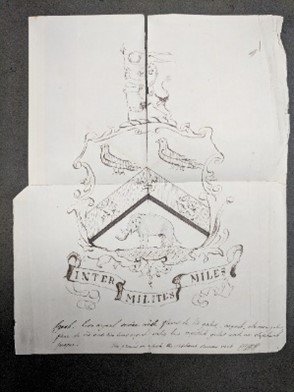

At the bottom of a box in London’s National Archives lies a sketch of a coat of arms – complete with a rather awkward elephant – collaborated on by two siblings in 1844, Sir Harry Smith and Jane Alice Sargant [1]. While Smith, a Waterloo hero turned colonial governor, has largely been remembered by posterity, his prolific writer-sister is long out of print. Without Sargant’s texts, spanning approximately 1817 to 1857, we lose part of the picture of how women writers reinvented themselves throughout the long nineteenth century, seen in the remarkable diversity of her publications: war poems and sentimental sonnets, political pamphlets and plays, domestic novels and conduct books, and short stories for the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Even in the latter, published near the end of her life, soldiers and battlefield glory play a central role in Sargant’s writing.

Sir Henry George Wakelyn “Harry” Smith, baronet, of Aliwal. Wikipedia Commons.

Sargant’s close relationship with her military brother and her desire that he should “distinguish” himself in Britain’s colonial campaigns form one pillar of her literary output, which raises a series of questions for recovery work: How did women like Sargant contribute to the corpus of military literature? What can her conservativism, and later neglect, tell us about reading practices in the long nineteenth century? How might her colonial ties prompt different and better recovery practices? This post merges the interests of the K-SAA’s Uncovering the Archives and Re-Thinking Romanticism series by sharing materials that might promote Sargant to a marginal position in the canon while problematizing recovery efforts, my own included, centered on white women.

Although none of Sargant’s handwritten materials seem to have survived beyond the coat of arms sketch, many of her books and pamphlets are housed at Harvard and the British Library. The British Library digitized her first and only poem collection, so readers can examine the two editions of 1817 and 1818 as well as the long list of subscribers [2]. The preface to Sonnets and Other Poems explains that “severe domestic afflictions” led her to publish, and unverified accounts suggest she was deserted by the elusive Mr. Sargant (x). Indeed, The Gentleman’s Magazine extensively linked Sargant to Charlotte Smith, positing that Sargant “is almost as mournful, but not quite so querulous; she is less poetical, but more natural [than Smith]” [3] Still, for all the attention to “anxiety” and “tranquility” in Sargant’s preface, a firing of martial glory can be seen throughout the collection (xi). Poems appear in the mouths of marching soldiers, leading generals, and even poverty-stricken disbanded soldiers. Often, home front and front lines are merged as in “To My Brother.”

The customary language of “honour” and “glow[ing] battle,” along with the suggestion of Britain’s divine protection, aligns Sargant’s sonnet with the myriad poems that filled newspapers throughout the Napoleonic Wars (5, 8). The topical nature of such poems becomes permanent, however, through Sargant’s continued attention to war years after Britain’s great triumph at Waterloo. Sargant’s symbiotic relationship with her brother’s career, which Stephen Behrendt also comments on [4], produced poems that collapse war into a shared Wordsworthian “spot” for brother and sister, men and women (13). Her strategies to do so prefigure women’s World War I poetry, such as Vera Brittain’s “To My Brother,” which begins, “your battle wounds are scars upon my heart.”

At the same time, this shared “spot” for men and women to experience war is predicated on and fueled by Britain’s imperialistic ambitions. Out of the nationalistic fervor of Waterloo grew, especially in the Smith-Sargant family, a desire to establish Britain’s influence more permanently across the globe. By the time Smith retires, in ignominy, from his position as Governor of the Cape of Good Hope in 1852, his sister had saved hundreds of his letters from India to South Africa. Smith, or his biographers, did not seem to preserve any of Sargant’s letters, though one relaying their father’s death made it into print as an appendix to her brother’s autobiography [5].

One of Smith’s letters to Sargant, held in London’s National Archives. WO 135/3.

We can infer, however, from Smith’s letters to his sister that Sargant encouraged her brother’s martial display against the colonized people of India. As Smith reminds her in his letter of February 1846, shortly before he was awarded a baronetcy for subduing the Sikh Empire, “You always so desired I should distinguish myself. I have now gratified you” (Autobiography 399).

The siblings’ jingoistic attitude extends to their collaboration on the coat of arms. Smith critiques Sargant’s elephant because its “hind legs are all wrong” and worries about the lions being too “preposterous” (390). All the while they appropriate a symbol considered divine to the various groups on the Indian subcontinent that Smith’s forces subdue, and whose leaders Smith belittles in letters to his sister. The co-opted coat of arms becomes a dreadful license for Smith when he declares the Kaffraria region – inhabited at this time by the Xhosa-speaking people of South Africa – as British territory in 1847. As he explains his decisions to Sargant during an uprising in 1851, “I am…in the midst of a war with cruel and treacherous and ungrateful savages and renegade and revolted Hottentots…My study has been to ameliorate their condition from brutes to Christians, from savages to civilized men” (271-3).

Sargant’s Remarks Occasioned by Strictures in the Courier and New York Enquirer of December 1852. Held at Harvard and now digitized by Google. Widener Q598.

Strikingly, the very next year Sargant pens a pamphlet admonishing women in America for not helping end slavery in their country [6]. She calls on women “to refine the African” instead of becoming “tainted” by them, perhaps, she implies, through sexual relationships (“Remarks” 27). She uses the familiar figure of “the negro mother,” too, to appeal to pity while offering white American women political “influence [as] a substitute for more direct rights” (40, 38). Like his play-by-play accounts of battle, Smith’s imperialistic lens seems to have shaped much of Sargant’s poetry and prose.

Today Smith’s coat of arms can be found on the school to which he gave his name in the UK, while Sargant, who once ran a school in London, has disappeared. The tendency in recovery work has been – as has certainly been the case with me – to fill gaps in the canon in terms of gender, often focusing on white women. While I am far from having all the answers, I use Sargant and her brother as an example of the critical context that should be explored alongside an author being resurrected simply because they are little-known. Doing so creates more space to critique white, colonial narratives and points researchers towards the voices and experiences of marginalized groups. From here, then, we might trace Sargant’s connections to settlements in New Zealand or shed light on Smith’s wife, Juana, who was displaced from her home in Spain by the Peninsular Wars. Recovery efforts also need to foreground more of the voices from India and South Africa that Smith spoke so loudly over.

I am grateful to the K-SAA for the space and support to explore Jane Alice Sargant and the stakes of recovery work more fully.

Dr. Emily J. Dolive

Emily Dolive received her PhD from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in 2019 and recently completed a postdoctoral fellowship in Baylor University’s English Department. The main question that guides her research asks how Romantic-era women poets engaged with political conflicts, particularly during the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars. She is now teaching at Eastside Catholic School, a college preparatory academy in Washington.

Follow her on Twitter here.

All images courtesy of Dr. Dolive. With many thanks to the National Archives for their permissions.

References

[1] Sir Harry Smith Correspondence. WO 135/3. National Archives, London.

[2] Jane Alice Sargant, Sonnets and Other Poems. London, George Smallfield. 1817. http://access.bl.uk/item/viewer/ark:/81055/vdc_00000002BE54

[3] W.B. Chelsea “25. Review of Sonnets and Other Poems.” The Gentleman’s Magazine. August 1817, 151-3.

[4] Behrendt, Stephen C. British Women Poets and the Romantic Writing Community. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

[5] Sir Harry Smith, The Autobiography of Lieutenant-General Sir Harry Smith. Edited by G.C. Moore Smith. London, John Murray. 1903. https://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/hsmith/autobiography/harry.html

[6] Remarks Occasioned by Strictures in the Courier and New York Enquirer of December 1852, Upon the Stafford-House Address: in a letter to a friend in the United States. London: Hamilton, Adams. 1853. Widener Q598. Widener Library, Harvard University.

Additional Resources

“Ely House and Jane Alice Sargant.” St. Mary’s Lodge. http://www.stmaryslodge.co.uk/lordship-rd-villas.php

“Jane Porter to Jane Alice Sargant, 21 June 1822.” In Her Hand: Letters of Romantic-Era British Women Writers in New Zealand Collections. Otago Students of Letters, English Department, University of Otago. 2013. 88. https://www.otago.ac.nz/english-linguistics/otago089415.pdf

Vetch, R.H. “Sir Henry George Wakelyn [Harry] Smith, baronet, of Aliwal.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Revised by John Benyon. 03 January 2008.