Louisa Albani on 'Mary Shelley's Lost Story' and her upcoming exhibition

The following blog post is by Louisa Albani: artist, educator, and independent publisher. Her new exhibition and pamphlet celebrate the 20th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley's Maurice or the Fisher's Cot. Do you know the tale behind this fascinating manuscript? Read more below... and if you're in London this October, you can visit the exhibition at Keats House.

Mary Shelley’s Lost Story

A literary art project inspired by Maurice or The Fisher’s Cot

To be exhibited at Keats House Museum, 12–19 October 2018

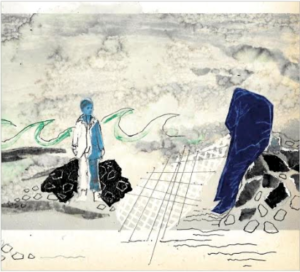

To celebrate the 20th anniversary of the first publication of Maurice or The Fisher’s Cot, I wanted to create an art project that encourages audiences to imaginatively engage with a lesser known work by Mary Shelley – to bring the words ‘back to life’ through visual storytelling. ‘It’s a small work, but touched with the same spirit as the greater ones it stands among’ writes Claire Tomalin in her Introduction to Mary Shelley’s Maurice or The Fisher’s Cot published in 1998, a year after the story was found hidden away in a library packing case, in an ancient house deep in the Apennine hills of Italy. A story lost to history for over 100 years, and discovered by Cristina Dazzi, her husband a descendant of Laurette, the girl that Mary Shelley originally wrote the tale for. There is something magic about the synchronicity of the creation and discovery of Mary Shelley’s lost story. Laurette was the daughter of Lady Margaret Mountcashell, who as a teenage girl had been tutored by Mary Wollstonecraft, Shelley’s mother. Mary’s Italian journals mention that she has written the story, and a letter from William Godwin, her father and a publisher of children’s books, refers to the manuscript being too short for publication. But the narrative itself remained a mystery. On reading the story for the first time, Tomalin describes being struck by its ‘melancholy’. At the time of writing Maurice, Mary Shelley had already eloped to Europe with Percy Bysshe Shelley whilst still a teenager, following an early life in London growing up without a mother. By 1820, she was twenty three years old and had coped with the death of three of her children. A nomadic existence with Percy travelling around Italy, coupled with maternal grief, offer insight into the themes of lost children and loss of identity in Mary’s story for Laurette.

‘It’s a small work, but touched with the same spirit as the greater ones it stands among’ writes Claire Tomalin in her Introduction to Mary Shelley’s Maurice or The Fisher’s Cot published in 1998, a year after the story was found hidden away in a library packing case, in an ancient house deep in the Apennine hills of Italy. A story lost to history for over 100 years, and discovered by Cristina Dazzi, her husband a descendant of Laurette, the girl that Mary Shelley originally wrote the tale for. There is something magic about the synchronicity of the creation and discovery of Mary Shelley’s lost story. Laurette was the daughter of Lady Margaret Mountcashell, who as a teenage girl had been tutored by Mary Wollstonecraft, Shelley’s mother. Mary’s Italian journals mention that she has written the story, and a letter from William Godwin, her father and a publisher of children’s books, refers to the manuscript being too short for publication. But the narrative itself remained a mystery. On reading the story for the first time, Tomalin describes being struck by its ‘melancholy’. At the time of writing Maurice, Mary Shelley had already eloped to Europe with Percy Bysshe Shelley whilst still a teenager, following an early life in London growing up without a mother. By 1820, she was twenty three years old and had coped with the death of three of her children. A nomadic existence with Percy travelling around Italy, coupled with maternal grief, offer insight into the themes of lost children and loss of identity in Mary’s story for Laurette. Maurice is about a boy who is abducted by a sailor’s wife who longs for a child. He runs away to escape the husband’s cruelty, and eventually finds refuge in a fisherman’s cot on the south Devonshire coast. As the tale unfolds, we discover that the boy’s journey ‘back home’ is not just centred on the value of family, but also about how a sense of belonging is inextricably linked to a deep connection with the natural world. As Colin Carman points out, the ‘weather-beaten cot’ is a marginal place where land meets sea, where the spray of the sea is ‘dashed against the windows’, the tide almost reaches the door, and the roof is made of lichen and moss. The ‘cot’ provides Maurice with a feeling of security but the boy and Barnet the fisherman have to adapt to an all-male household and brave the elements in order to survive. After Barnet’s wife dies, the fisherman has no one to light the fire and prepare his supper when he returns from the sea. Maurice takes over this role, placing a candle at the window to direct him home, as well as mending the nets. There is an evolutionary thread running through Mary Shelley’s story, that points to the need for people to learn to live in environmentally challenging habitats, as well as adjust to new ways of what it means to be ‘family’ and to belong.

Maurice is about a boy who is abducted by a sailor’s wife who longs for a child. He runs away to escape the husband’s cruelty, and eventually finds refuge in a fisherman’s cot on the south Devonshire coast. As the tale unfolds, we discover that the boy’s journey ‘back home’ is not just centred on the value of family, but also about how a sense of belonging is inextricably linked to a deep connection with the natural world. As Colin Carman points out, the ‘weather-beaten cot’ is a marginal place where land meets sea, where the spray of the sea is ‘dashed against the windows’, the tide almost reaches the door, and the roof is made of lichen and moss. The ‘cot’ provides Maurice with a feeling of security but the boy and Barnet the fisherman have to adapt to an all-male household and brave the elements in order to survive. After Barnet’s wife dies, the fisherman has no one to light the fire and prepare his supper when he returns from the sea. Maurice takes over this role, placing a candle at the window to direct him home, as well as mending the nets. There is an evolutionary thread running through Mary Shelley’s story, that points to the need for people to learn to live in environmentally challenging habitats, as well as adjust to new ways of what it means to be ‘family’ and to belong. There is also a sense of the importance of ‘place’ and how significant it can be in relation to forming bonds. Maurice first meets Barnet on a piece of rock that forms a kind of seat, mending his nets. After Barnet dies, Maurice meets the traveller as he is sitting on the same rock looking out to sea. The ‘cot’ and the ‘rock’ seem to symbolise a sense of continuity in relation to the attachments he forms. As an adult, Maurice continues to reinforce this. After a time, the cot collapses, so he builds another one not in the same place but nearby, ‘where he placed to live a poor fisherman and his two children’. Whilst passing on his good fortune to those less fortunate, he also protects the ‘place’ where he felt loved and secure as a boy. Maurice’s engagement with ‘place’ in the story empowers him to reclaim old bonds and create new ones. How extraordinary, then, that the story itself was lost for many years, protected in an ancient house, only to be rediscovered by a descendant of Laurette. The theme of ‘spirit of place’ permeates not only the narrative of Maurice or The Fisher’s Cot, but the history of the manuscript itself.I would like to thank Claire Tomalin for her support and encouragement with this art project.

There is also a sense of the importance of ‘place’ and how significant it can be in relation to forming bonds. Maurice first meets Barnet on a piece of rock that forms a kind of seat, mending his nets. After Barnet dies, Maurice meets the traveller as he is sitting on the same rock looking out to sea. The ‘cot’ and the ‘rock’ seem to symbolise a sense of continuity in relation to the attachments he forms. As an adult, Maurice continues to reinforce this. After a time, the cot collapses, so he builds another one not in the same place but nearby, ‘where he placed to live a poor fisherman and his two children’. Whilst passing on his good fortune to those less fortunate, he also protects the ‘place’ where he felt loved and secure as a boy. Maurice’s engagement with ‘place’ in the story empowers him to reclaim old bonds and create new ones. How extraordinary, then, that the story itself was lost for many years, protected in an ancient house, only to be rediscovered by a descendant of Laurette. The theme of ‘spirit of place’ permeates not only the narrative of Maurice or The Fisher’s Cot, but the history of the manuscript itself.I would like to thank Claire Tomalin for her support and encouragement with this art project.

- Louisa Amelia Albani 2018

You can purchase the pamphlet edition of Louisa Albani's artwork here. You can visit the temporary exhibition of 'Mary Shelley's Lost Story' from 12-19 October 2018 at Keats House, Hampstead. Entry to the exhibition is included in the admission price for entry to the house. Opening hours and prices here.